Written by J.C. Lee & Julius Onah

The fundamental conflict in Luce starts when a young man’s essay based on the work of the anti-colonialist psychoanalyst from Martinque, Frantz Fanon, is interpreted as a sign of deviancy and as a potentially terroristic threat to the school and others. The film spends very little time exploring or articulating the work of Fanon or colonialism other than to use it as way of saying “don’t be like that radical black man who advocates violence against his enemies”. Julius Onah, who also directed The Cloverfield Paradox, and the screenwriters ignore Fanon’s work as an advocate for libratation of colonized people. As Angela Davis said in the film The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 “When someone asks me about violence, I just find it incredible, because what it means is that the person who’s asking that question has absolutely no idea what black people have gone through, what black people have experienced in this country, since the time the first black person was kidnapped from the shores of Africa.” Fanon wrote that in the eyes and systems of knowledge of Western colonizing countries the colonized subject is a “non-being”. And thus as “non-being” their only response to their subjugation is to wage a one sided struggle against it, violent or otherwise (Thorn, 2018). In misinterpreting Fanon’s work Luce does a disservice to its characters and to its audience. Which brings into focus who is the film actually catering to? It does not seem to exist to legitimize the anti-colonial struggles of people of color nor does it seem to exist to legitimize the struggles of minority students within the white supremacist education system in the United States. Instead, it tries to thread a very fine line which reads as legitimizing an American liberal middle class ontological view of the world which is antagonistic to liberation for working class people of color.

Capitalist education are sites of proliferation of bourgeois knowledge. Where do these middle-class ideas such as bourgeois respectability, acceptability, and the propensity of the colonized subject to revert to violence or the ideas that violence is always illegitimate come from? As the philosopher Karl Marx wrote in The German Ideology “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it. The ruling ideas are nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relationships, the dominant material relationships grasped as ideas.” In Cape Verde and GuineaBissau, for example, needing local allies to rule its subjects the interest of the Portugese colonial state resulted in the entrenching, protecting, and enhancement of the cultural influence of the indigenous ruling class of Cape Verde and Guinea Bissua (El Nabolsy, 2019). Luce’s protection, entrenchment, and enhancement of the American dream and liberal ideas Americans have about America is the expression of Marx’s statement. The exceptional individuals; the Zuckerberg, the Barack Obama, become evidence of the greatness of America while America is in fact a nightmare. The empire does not tell an honest history of itself. It is how it survives. The wealth of America hides the poverty of America. Those who complain about America; black people, indigenous people, anti-colonialists, become the enemy of America. The empire reenforcing the history that helps it survive.

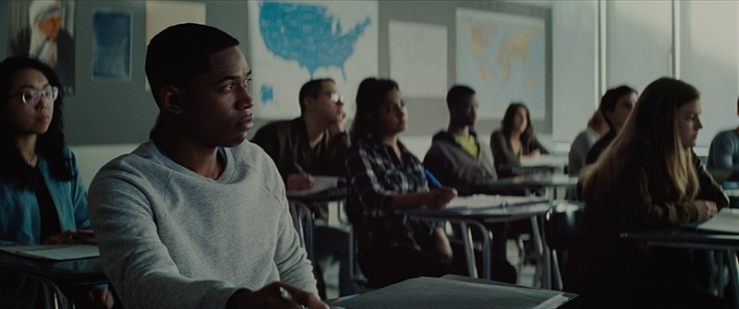

Luce Edgar, the title character, is an icon of modernism and America. Luce centralises the idea of objectivity, individualism, and reason as the best way to solve conflicts. The notoriously cryptic philosopher and professional racist Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel claimed that the thing which defines modernity from other epochs is “the axiological importance assigned to an individual’s ability to choose what to do with their lives” (El Nabolsy, 2019). This is also very much the idea of America. In America people are free to be who they want to be. Or at least that’s what Luce says. But you also believe it too, especially watching as an American, every cultural production and educational product is fabricated to explain and reexplain to you how America is unique among nations in the ability to grant its inhabitants a second chance. Never mind that anyone can “start over” anywhere. What people mean when they say this is in America is you can leave behind your history. Of course this liberation from one’s past is only available to some. A brown or black immigrant is always a brown or black immigrant, always an outsider. What ever was going on in the place you came from, that is not important, the only thing important in America is capitalism. What people mean when they say this in America is you can reinvent yourself, be yourself as long as you have money and the means. Money and means are easier to find in America, it is the center of capitalist empire afterall. Where does money go when its not working? To the banks and corporations in America of course. Never mind that with money and means and an immense amount of luck, you can reinvent yourself anywhere. Luce, as a character, is the archetype of the mythology of America as the land where greatness is possible and the ideology of modernism that primacy personal autonomy and centralizes humans as makers of their own histories and identities. After all, he is young man who survived war in Eritrea and overcame post-conflict PTSD to become his schools most iconic individual, destined to do great things.

Luce Edgar, the title character, is an icon of modernism and America. Luce centralises the idea of objectivity, individualism, and reason as the best way to solve conflicts. The notoriously cryptic philosopher and professional racist Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel claimed that the thing which defines modernity from other epochs is “the axiological importance assigned to an individual’s ability to choose what to do with their lives” (El Nabolsy, 2019). This is also very much the idea of America. In America people are free to be who they want to be. Or at least that’s what Luce says. But you also believe it too, especially watching as an American, every cultural production and educational product is fabricated to explain and reexplain to you how America is unique among nations in the ability to grant its inhabitants a second chance. Never mind that anyone can “start over” anywhere. What people mean when they say this is in America is you can leave behind your history. Of course this liberation from one’s past is only available to some. A brown or black immigrant is always a brown or black immigrant, always an outsider. What ever was going on in the place you came from, that is not important, the only thing important in America is capitalism. What people mean when they say this in America is you can reinvent yourself, be yourself as long as you have money and the means. Money and means are easier to find in America, it is the center of capitalist empire afterall. Where does money go when its not working? To the banks and corporations in America of course. Never mind that with money and means and an immense amount of luck, you can reinvent yourself anywhere. Luce, as a character, is the archetype of the mythology of America as the land where greatness is possible and the ideology of modernism that primacy personal autonomy and centralizes humans as makers of their own histories and identities. After all, he is young man who survived war in Eritrea and overcame post-conflict PTSD to become his schools most iconic individual, destined to do great things.

Luce is a film with so many different conflicts its as if it was created by a student of anti-colonial theory, intersectionality, and feminism while also being created by someone who failed every class on those subjects. The film hides its true narrative behind twisting PSYOP walls of obfuscation that would make Shonda Rhimes blush. It is explained he is a refugee from Eritrea and was adopted by Amy and Peter Egars from a refugee camp as small child. The timeline is little muddled as Luce is between 16-18 years old and the Eritrean War for Independence ended in 1991. So its unlikely he was in a refugee camp in Eritrea during the war but the film does not explain what happened to him other than to say he needed several years of therapy to get over his trauma. As a person who was adopted from Somalia I felt I shared a lot with Luce and the emotions surrounding him. Without exploring his integration into America I am hesitant to believe Luce would so easily turn away from his past and his Eritreanness. No matter how difficult that past might that past offers information on where he comes from. It is evidence that he comes from a place with history and a people with his. It is proof he was born. Without that past, in America he has to make himself into a being from scratch alone. Luce plays with the fact that within America blackness itself is inherently transgressive. This is not too dissimilar from Fanon remarking that colonialism had so extensively corrupted white French people’s minds that just being present as a black person near them resulted in white French people verbally assaulting him (Thorn, 2018).

The colonized does not come into being until introduced to their inferiority by the colonizer. As Fanon states “If he is a Malasays it is because the white man has come, and if at a certain stage he has been led to ask himself whether he is indeed a man, it is because his reality as a man has been challenged. In other words, I begin to suffer from not being a white man to the degree that the white man imposes descrimination on me, makes me a colonized native” (Fanon, 1967, pp. 88). The colonizer demands the native bring themselves into his own ontological and epistemological world. After being told he is a parasite and has no use in the world the native “will quite simply try to make [themselves] white; that is […] compel the white man to acknowledge [them]”. Fanon wrote in Black Skin, White Mask while some colonized subjects reject their colonizers others respond to their subjugation by trying to be more like their colonizers. By entering into history as Westernized African or Asian, the colonized subject expects the colonizer to recognize them finally as a full person. Of course, he does not.

Luce Edgar’s teacher Harriet Wilson exemplifies Marx’s description that the function of “educational institutions in industrial capitalism was essentially to reproduce existing class and other structures of inequality across time” (Springer & Benjamin, 2019). Luce Edgar, Stephanie Kim, DeShaun Meeks, and other characters experience constant racial microagressions related to their identies as non-white people, as women, and the expecations as well as the responsiblities people with those identies have to other people with those identities. Essentially, there are two related but contrasting groups within in Luce; one is adults and all the ideas and expectations they have on their children contrasted with their own expectations on themselves about their responsibilities as parents and or teachers, the other is the students and their ideas and expectations about who they are. In a world of linear time, where a misstep or mistake in the present or past can dramatically effect the success or failure of an individual in the future, the adults are hyper focused on “doing the right thing” and not “ruining” or “breaking” their children. At the same time Octavia Spencer plays the sole black teacher that is not the sports coach, and her character Harriet Wilson has already experienced the expectations or lack of expectations society and its institutions have for black and non-white bodies. Amy and Peter, Luce’s white parents. and Harriet Wilson are so use to thinking within the ideological confines of acceptable middle-class white American ideas about modernity and success within the capitalist America that they are unable or unwilling to consider the colonial subject Fanon was talking about. If a person’s identity is a function of their history, then at same time a person with ahistorical view of their own history is unable to recognize the reality of their own world. The irony of people who radiate fervent reverence to America’s mythical foundation and American nationalism while denigrating violence as a method of liberation from an oppressor escapes the parents, the teacher, the principal, as well as the student. When Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called America “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today” he was confronting America’s love of colonialism and its love of colonial violence. Not only was the United States “using massive doses of violence to solve its problems [in Vietnam], to bring about the changes it wanted”, violence is the way the United States came into being (King, 1967). America is often though as a colony, but not the way African countries or Asian countries were and are colonies. America was a colony which liberated the colonizers from the administrators of their colonization project. America did not and has not sought to liberate its colonized black populations or its indigenous populations, to do so would be against its survival. As such, it would be reasonable to understand a nation which was not only born as a racist colonial project but who’s citizens were the agent of that racist colonization project would not recognize the rights of brown or black people to be free like them.

Luce Edgar’s teacher Harriet Wilson exemplifies Marx’s description that the function of “educational institutions in industrial capitalism was essentially to reproduce existing class and other structures of inequality across time” (Springer & Benjamin, 2019). Luce Edgar, Stephanie Kim, DeShaun Meeks, and other characters experience constant racial microagressions related to their identies as non-white people, as women, and the expecations as well as the responsiblities people with those identies have to other people with those identities. Essentially, there are two related but contrasting groups within in Luce; one is adults and all the ideas and expectations they have on their children contrasted with their own expectations on themselves about their responsibilities as parents and or teachers, the other is the students and their ideas and expectations about who they are. In a world of linear time, where a misstep or mistake in the present or past can dramatically effect the success or failure of an individual in the future, the adults are hyper focused on “doing the right thing” and not “ruining” or “breaking” their children. At the same time Octavia Spencer plays the sole black teacher that is not the sports coach, and her character Harriet Wilson has already experienced the expectations or lack of expectations society and its institutions have for black and non-white bodies. Amy and Peter, Luce’s white parents. and Harriet Wilson are so use to thinking within the ideological confines of acceptable middle-class white American ideas about modernity and success within the capitalist America that they are unable or unwilling to consider the colonial subject Fanon was talking about. If a person’s identity is a function of their history, then at same time a person with ahistorical view of their own history is unable to recognize the reality of their own world. The irony of people who radiate fervent reverence to America’s mythical foundation and American nationalism while denigrating violence as a method of liberation from an oppressor escapes the parents, the teacher, the principal, as well as the student. When Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called America “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today” he was confronting America’s love of colonialism and its love of colonial violence. Not only was the United States “using massive doses of violence to solve its problems [in Vietnam], to bring about the changes it wanted”, violence is the way the United States came into being (King, 1967). America is often though as a colony, but not the way African countries or Asian countries were and are colonies. America was a colony which liberated the colonizers from the administrators of their colonization project. America did not and has not sought to liberate its colonized black populations or its indigenous populations, to do so would be against its survival. As such, it would be reasonable to understand a nation which was not only born as a racist colonial project but who’s citizens were the agent of that racist colonization project would not recognize the rights of brown or black people to be free like them.

El Nabolsy, Z. (2019). Amílcar Cabral’s modernist philosophy of culture and cultural liberation. Journal of African Cultural Studies, 1–20. doi:10.1080/13696815.2019.1624155

Fanon, Frantz. (1967). Black Skin, White Masks (Markmann, C.L., Trans). New York, NY: Grove Press, Inc

King, M. K. (1967). Beyond Vietnam. Stanford University: The Martin Luther King, Jr.

Research and Education Institute. Retrieved from https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/beyond-vietnam

Springer, D., Benjamin, J. (2019). Groundings: A Revolutionary Pan-African Pedagogy for Guerilla Intellectuals In D. R. Ford (Ed.), Keywords in Radical Philosophy and Education. (pp. 210-225). Boston. Masseshecuts: Brill Sense.

Thorn, O. [Philosophy Tube]. (2018, Apr 27). Intro to Hegel (& Progressive Politics) [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OgNt1C72B_4